It’s not often when you get the drop on feral swine. I’m convinced they are some of the smartest wildlife in the state. I’m sure they use deductive reasoning during their everyday life. If hunted hard they turn nocturnal. If one or two are trapped, the others in the group that witnessed the door slam shut will never be trapped. If run by dogs, they quickly learn to never stop and fight, but to keep running and eventually wear down the chasing dogs or swim a river to get away. Those animals are smart rascals for sure.

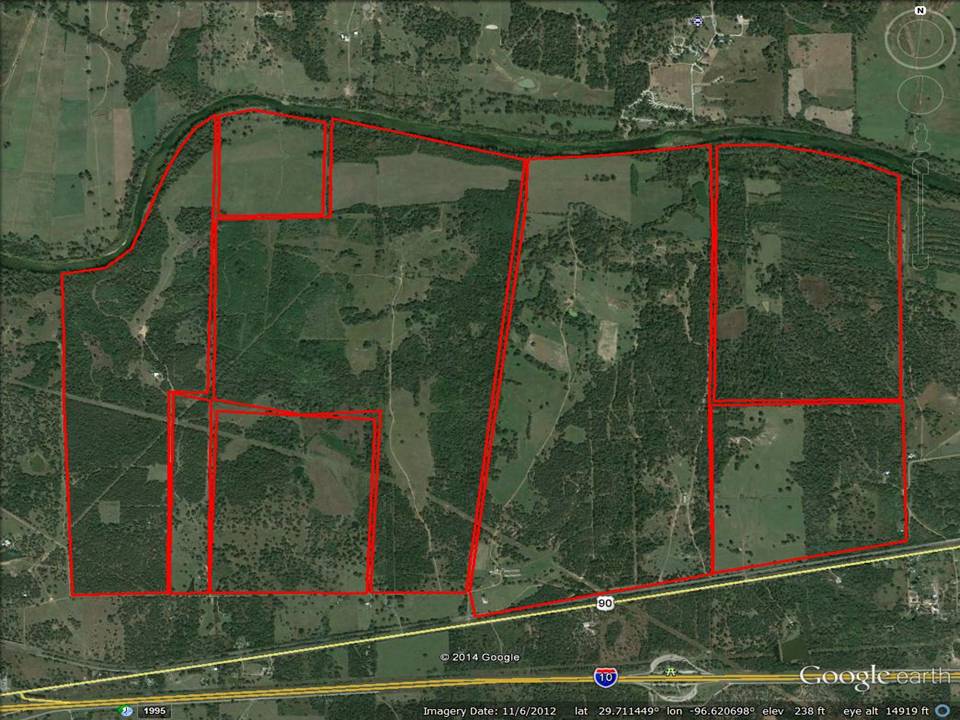

A couple of years ago I had a wonderful ranch leased for cattle near Rock Island, TX. The northern one-third of the property was wide open with the exception of a few scattered wild rose hedges. At one time, that section of the ranch was farmed for rice. The place was flat as a pancake.

While checking cattle one evening, I spotted a pair of coyotes trotting across the prairie about 500 yards away and made a mental note of it. I was more concerned with a corner of the field that had huge rooting holes torn through the turf. From the size of the holes, it looked to me as if it was a solo old boar. This got my blood up. It was time to wage war.

I learned a long time ago the swine are most active at night whenever the moon is straight up. It was several days past the full moon which would put the moon at its zenith around dawn. The next morning I left my house early, stopped in Columbus for a donut and coffee, and then cruised slowly towards the ranch. I had two rifles with me that morning. One was my old Winchester Model 70 30-06 that was built in 1937. This was for an old boar. The other was my dad’s Sako Vixen 222 magnum. This was for coyotes. I was set for anything.

It was a clear morning, cool. The eastern horizon was just turning silver and the tree line along Skull Creek looked like black lace against the sky. The pale yellow moon was straight up and added a misty glow to the land. I was oozing along the paved county road that bordered the eastern part of the ranch and thought I saw some black dots in the field with my naked eye. Binoculars showed me about 20 hogs milling about but drifting north. I knew with the sun on its way in about 30 minutes they would be off the property heading towards the nearest heavy timber on the Glascock Ranch. A steady south wind was blowing. My hunter instinct took over and I planned an ambush.

I quickly did a three-point turn on the narrow county road and headed to the NE corner of the property. Here was an old gate and gravel road that led into the middle of the pasture where an oil field location once stood. I inched down this road not wanting to make too much crunching noise as my tires rolled on the gravel road. The hogs were about 1,000 yards away and starting to travel towards me in a more determined manner. They had quit feeding and were heading home to their bedding area. My brown truck blended in with the old poisoned rose hedges that had turned a similar shade. I circled to the north of one of the clumps of dead brush, and nosed my truck into the hedge. Just the roof of my vehicle would be visible to the pigs. I grabbed both rifles, eased my door shut without making a noise, then I climbed into the back of the bed. I held the 30-06 in my hand and laid the little 222 magnum on the roof of my cab and waited. I felt like Davy Crocket with a spare musket leaning on the Alamo parapet looking at Santa Anna’s troops marching my way!

This was a perfect trap. The movement of the hogs looked like a long black snake weaving but heading directly to me. The wind was in my favor and my truck was hidden. I had two loaded rifles with roughly 20 hogs approaching on a wide open prairie and being in the back of my truck gave me a little elevation. This was going to be EPIC!

Closer and closer they came. I distinctly recall their ears were flopping as they trotted towards me. I had the crosshairs solid on the leader with no wobble on my hold when he got to within 25 yards of the truck and abruptly stopped. He lifted his head to study something that apparently seemed unusual to his beady pig eyes. Perhaps he could see a gleam from a small part of my windshield. The other pigs were bumping into each other as the whole group came to a stop. That was the last thing the leader saw. A 150 grain bullet crashed into its chest dropping him in his tracks. That was a layup shot.

When the rifle boomed, the herd exploded to action. Imagine a fireworks display and a star burst. That is what happened next—pigs of all sizes ran in every direction. I swung on a hog running to my left and dropped it. He was only 40 yards away. Another pig was running at about a 45 degree angle on my left side and about 75 yards out and I cut down on that one. When the bullet hit his ribs it did a flip and slid on its back in a cloud of dust and weed seeds. My fourth and last shot with the big rifle was a straight away hog that required no lead. This guy was out about 125 yards or so. Down it went. Four down with four shots and three were running! I was in a groove.

I laid down the empty 30-06 and snatched up the little Sako. Now I concentrated on the right side of the truck. By this time, the hogs were getting out there a bit, and I hate to admit it, but my first shot with the light rifle was a clean miss. I did not lead enough or stopped my swing. I corrected on my next attempt and rolled one that was almost 200 yards away. My third shot with the little 222 magnum hit a hog in its flank. This slowed the animal and gave me a chance with the final shot to dispatch it with a good hit to the chest. I took my time on the wounded hog and planted the little 55 grain bullet right on the heart. This last pig was laying about 250 yards away.

All of the above action took place in about 20 seconds. Now all was quiet except for the shrill ringing in my ears from the rifle reports. The air was spiced with burnt cordite. I watched the survivors racing across the prairie in the distance for a bit then checked the hogs I had just shot. All were still except for one that had a hind leg limply wind-milling the morning air in its last dying reflex escape attempt. Slowly the leg relaxed then all were still. There are no close neighbors to that ranch but if anyone heard the hot action, I bet they thought the Third Infantry Division was wading ashore. Eight fast paced shots bagged six. My first shot was standing the others running. One clean miss and one hog took two shots to put down for good. I was pleased and expect it to be a long time before that episode will be repeated, though I do carry more ammo now just in case.